Cutaneous genital schistosomiasis in a 6-year-old female child - case report and review

1 Dec 2024

Cutaneous genital schistosomiasis in a 6-year-old female child: case report and review

Authors: Baraka Michael Chaula [1] [2], and William John Muller [2] [3]

- Dermatology Unit-Mbeya Zonal Referral Hospital-Mbeya, Tanzania.

- University of Dar es Salaam-Mbeya College of Health and Allied Sciences, Mbeya, Tanzania.

- Department of Pathology-Mbeya Zonal Referral Hospital-Mbeya, Tanzania.

Abstract

Schistosomiasis affects millions of individuals worldwide. There are at least six species that can cause human schistosomiasis – Schistosoma haematobium, S. mansoni, S. intercalatum, S. guineensis, S. japonicum and S. mekongi. This disease more commonly leads to morbidity rather than mortality. We describe a 6-year-old girl with a multinodular plaque and swelling of the vulva. The lesion was asymptomatic but had increased in size and the patient reported no systemic symptoms. Schistosoma infection was confirmed via histopathological examination. Cutaneous schistosomiasis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of nodular lesions of the external genitalia.

Conflict of interest: None

Key words: Cutaneous schistosomiasis; vulva; female child

Introduction

Globally, more than 200 million people are affected by schistosomiasis, making it a common parasitic infection.1 The disease is more prevalent in South America, Asia, Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, but has also been reported in Europe2,3 and in travellers to the tropics.4 Certain pathogenic species can be found in specific geographic locations, e.g. Schistosoma mansoni in South America vs. S. japonicum and S. mekongi primarily in Asia.5

Human schistosomiasis represents a helminthic infection by trematodes, with freshwater snails serving as the intermediate hosts. The snails release larvae (cercariae) that mature into adults within the vasculature after penetrating the skin. Individuals can also be infected by ingestion of water contaminated by larvae.5

In humans, colonization may persist for years with secretion of eggs. An immune response to the trematodes, consisting of granuloma formation, can occur in both local and systemic schistosomiasis.6 In addition to S. haematobium, S. mansoni, S. intercalatum, S. guineensis, S. japonicum and S. mekongi, cutaneous involvement can also result from non-human species of Trichobilharzia and S. bovis (causing cercarial dermatitis).3,7 Trichobilharzia and S. bovis are hybrid between zoonotic and human species and are endemic in temperate regions of the world.3

Case report

A six-year-old female child was referred to our dermatology clinic with a ‘growth’ involving her vulva that had been noted 8 weeks prior. Her mother stated it had gradually increased in size but had not bled and was not painful or pruritic. There were no additional symptoms such as fever, lower abdominal pain, dysuria, haematuria or vaginal discharge. She was from an area with freshwater bodies close to her home and as a child she often swam in them. Blood chemistries and blood count were within normal limits, no ova were detected in her urine or stool, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status was negative.

On clinical examination, she had firm, non-tender, skin-coloured swelling of the left labia minora as well as a multinodular hyper- and hypopigmented plaque of the left labia majora with scarring (Figure 1). The latter was fixed to the underlying tissue. A few satellite papules were also present. There was no discharge or ulceration. Bilateral, mobile, non-tender inguinal lymphadenopathy was detected.

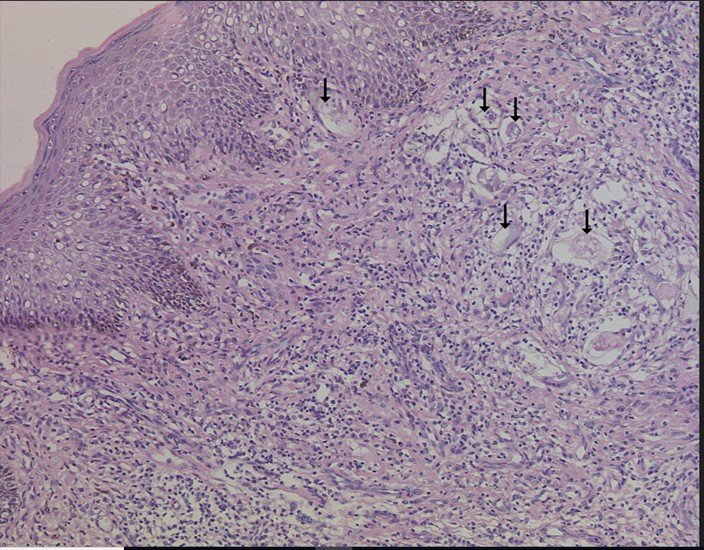

Histopathological examination of an incisional biopsy demonstrated multiple schistosomes within the dermis. There were also multiple epithelioid cell granulomas, Langhans giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells and scattered eosinophils within the dermis (Figure 2). Based on the clinical and histological findings, a diagnosis of cutaneous schistosomiasis was reached.

Discussion

In schistosomiasis, three stages of cutaneous manifestations have been described: pruritic cercarial dermatitis; Katayama syndrome with urticarial lesions; and in late disease, granulomatous lesions. The first two stages occur early on within 6 months of exposure.8

Cercarial dermatitis (swimmer’s itch) can occur as early as 30–60 min following exposure to larvae-infested freshwater. It follows the entry of Schistosoma larvae into the skin and can be seen in those who have not been previously exposed, including travellers.9 This presentation is not seen in children who grow up in endemic areas, in theory because they acquire maternal protective antibodies during their early months of life. In addition to a zosteriform papular pattern on the trunk, patients can develop recurrent flares, fever, peripheral blood eosinophilia and internal organ involvement (e.g. central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract) during the early stages.10

Late cutaneous schistosomiasis, defined as infection that occurs 6 months post-exposure tends to be rare. In most reported cases, the lesions are found in the perineal or genital region and they follow disease in other organs.9 Less commonly, the trunk is involved. Rarely, isolated cutaneous disease has been observed in the absence of constitutional symptoms or preceding urological disease.8

Classically, single or multiple nodules or papillomatous lesions are seen. Additional findings in women include ulceration of the vulva and vaginal discharge or bleeding as well as lower abdominal pain.11 Of note, cutaneous schistosomiasis has been described predominantly in females in their second and third decades of life.9 Confirmation of the diagnosis is routinely based on detection of eggs in faeces or urine or serological assays, but in the case of cutaneous involvement, histological substantiation is possible. Characteristics of the spines can assist in species identification – a terminal, lateral or minute spine represents S. haematobium, S. mansoni and S. japonicum, respectively.12

Although topical corticosteroids and/or antihistamines are often prescribed for cercarial dermatitis, antihistamines with or without systemic corticosteroids can be used for acute schistosomiasis; sometimes praziquantel is started at this stage, taking into account the risk of an allergic reaction. In chronic disease, dosages and frequencies vary, e.g. in African and South American schistosomiasis, the single dose is 40 mg/kg whereas for S. japonicum and S. mekongi it is 60 mg/kg. If an allergic reaction is suspected, the dose is divided. The cure rate can be increased from 80% to 100% if the single dose regimen is repeated for 2 consecutive days after 6–12 weeks.13

Repeat examination of stool and urine should be performed 6 weeks after completion of systemic therapy. Although cutaneous lesions can resolve within 6 months, calcification of ova may lead to persistence. Additional evidence of cure includes resolution of peripheral eosinophilia. Genital schistosomiasis can lead to an increased risk of transmission of other diseases such as HIV and is associated with a risk of ectopic pregnancies and infertility owing to fallopian tube blockage. To avoid stigmatization and alleviate anxiety, the non-sexual transmission of genital schistosomiasis should be explained.13

Follow the article content and flow

Conclusion

Our case is thought to be unique in that the patient was a young female child with no history of preceding systemic or constitutional symptoms based on her clinical history. She was diagnosed as having isolated cutaneous disease, based on the histological findings of her skin biopsy plus negative urine and stool examination for schistosomiasis (we were unable to perform a serological test). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of cutaneous female genital schistosomiasis in a child from Tanzania. Unfortunately, our patient was lost to follow-up before commencement of therapy and therefore we are unable to report on her treatment and clinical outcome.

References

- Utzinger J, Raso G, Brooker S et al. Schistosomiasis and neglected tropical diseases: towards integrated and sustainable control and a word of caution. Parasitology 2009; 136:1859–74.

- Bustindy AL, King CH. Schistosomiasis. In Manson’s Tropical Diseases (Farra J ed.), 23rd edn. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2014; 698–725.

- More H, Holtfreter MC, Alliene JF et al. Introgressive hybridizations of Schistosoma haematobium by Schistosoma bovis at the origin of the first case report of schistosomiasis in Corsica (France, Europe). Parasitol Res 2015; 114:4127–33.

- Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop 2000; 77:41–51.

- Lupi O, Downing C, Lee M et al. Mucocutaneous manifestations of helminth infections: trematodes and cestodes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73:947–57.

- Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet 2014; 383:2253–64.

- Brant SV, Andrew N, Cohen AN et al. Cercarial dermatitis transmitted by exotic marine snail. Emerging Infect Dis 2010; 16:1357–65.

- Iriarte C, Marks DH. Cutaneous schistosomiasis: epidemiological and clinical characteristics in returning traveler. Int J Dermatol 2023; 62:376–3.

- Leman JA, Small G, Wilks D, Tidman MJ. Localized papular cutaneous schistosomiasis: two cases in travellers. Clin Exp Dermatol 2001; 26:50–2.

- Davis-Reed L, Theis JH. Cutaneous schistosomiasis: report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42:678–80.

- Kaizileghe GK, Kiritta R, Chuma C et al. Female genital schistosomiasis a neglected differential of cervical precancerous lesion: a wake-up call for on-job training for health care workers in endemic areas. Austin J Clin Case Rep 2022; 9:1241.

- Kick G, Schaller M, Korting HC. Late Cutaneous schistosomiasis representing an isolated skin manifestation of Schistosoma mansoni infection. Dermatology 2000; 200:144–6.

- Ritcher J. Cutaneous Manifestations of schistosomiasis. In: Pigmented Ethnic Skin and Imported Dermatoses. A Text Atlas (Orfanos CE, Zouboulis CC, Assaf C, eds). Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2018;149–53.