Diagnostic clues of skin ulcers. Part I

1 Dec 2024

Diagnostic clues of skin ulcers. Part I: general concepts and ulcers of non-infectious aetiology

Author: Cristina Galván-Casas

Dermatology Unit, University Hospital of Mostoles, Madrid, Spain.

Skin Neglected Tropical Diseases and Sexually Transmitted Infections Unit, Fight Infections Foundation, University Hospital Germans Trías i Pujol, Barcelona, Spain.

Abstract

Skin ulcers have varying aetiologies, both infectious and non-infectious. The clinician caring for patients with skin ulcers faces multiple difficulties in establishing the correct diagnosis as the clinical signs of different ulcers can be very similar, regardless of their pathophysiological cause. Also the lack of the defence barrier of intact skin leads to contamination or actual infection by multiple micro-organisms. Recognizing the clinical and epidemiological clues of different ulcers is the first step in trying to diagnose the cause and decide on the most appropriate confirmatory tests. Venous, arterial, neuropathic and sickle cell anaemia-associated ulcers are of non-infectious aetiology, whereas tropical ulcer, melioidosis, cutaneous diphtheria, Buruli ulcer, yaws and leishmaniasis are caused by infectious agents. This paper is one of a series of two articles. In this first part, general concepts of ulcer care and the main characteristics or clinical clues of ulcers of non-infectious origin that may indicate the underlying aetiology, appropriate diagnostic tests and management and treatment are discussed. Part II, for later publication, will address the features of ulcers caused by an infection.

Conflict of interest: None

Key words: Skin ulcer; non-infectious skin ulcer; skin ulcer diagnosis; skin ulcer treatment

Key learning points

- A skin ulcer (lack of continuity of skin) is a clinical sign caused by many different aetiologies.

- Clinical examination of the ulcer, as well as other clinical and epidemiological clues, are essential for determining the cause and for guiding subsequent diagnostic tests and treatment.

- Ulcers tend to contain numerous micro-organisms, even those where the primary cause is non-infectious.

Introduction

Ulcers are the result of the breakdown of the surface of previously normal skin or following an inflammatory process in the skin triggered by an infectious or non-infectious cause. Ulcers with different pathophysiological causes can share very similar clinical signs, and the lack of the defence barrier of the intact skin leads to contamination by multiple micro-organisms. Bacteria present in the ulcer may be the primary aetiological cause. On the other hand bacteria may be present as a result of subsequent contamination, colonization or as an actual infection whereby bacterial tissue invasion induces physiological consequences that lead to delayed healing and ulceration.1 Non-infectious causes of ulcers include trauma, burns, bites, stings, systemic diseases and drugs. The most common causes of chronic leg ulcers are chronic venous insufficiency, peripheral arterial disease and diabetic neuropathy. In ulcers caused by infections, the agents may include multiple bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, protozoa, parasites and viruses.

The prevalence of systemic pathology and the distribution of infectious agents varies depending on geographical and sociocultural settings. In Part I and Part II, we will analyse non-genital skin ulcers that are more characteristic or prevalent in different areas. We will focus on the clinical clues to help determine the cause of the ulcer, appropriate diagnostic tests, and subsequent control and treatment strategies.

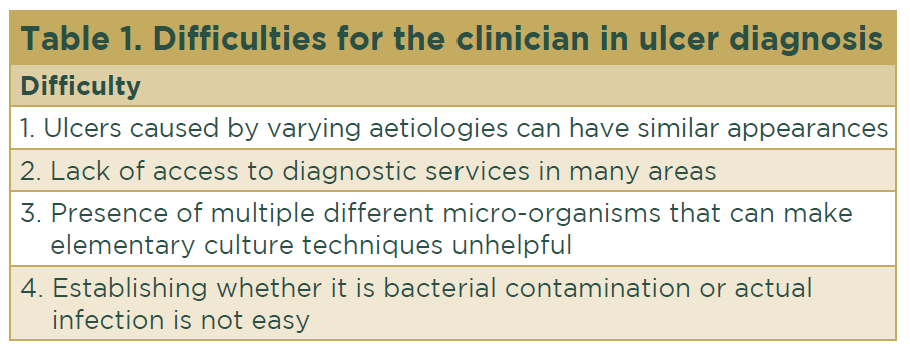

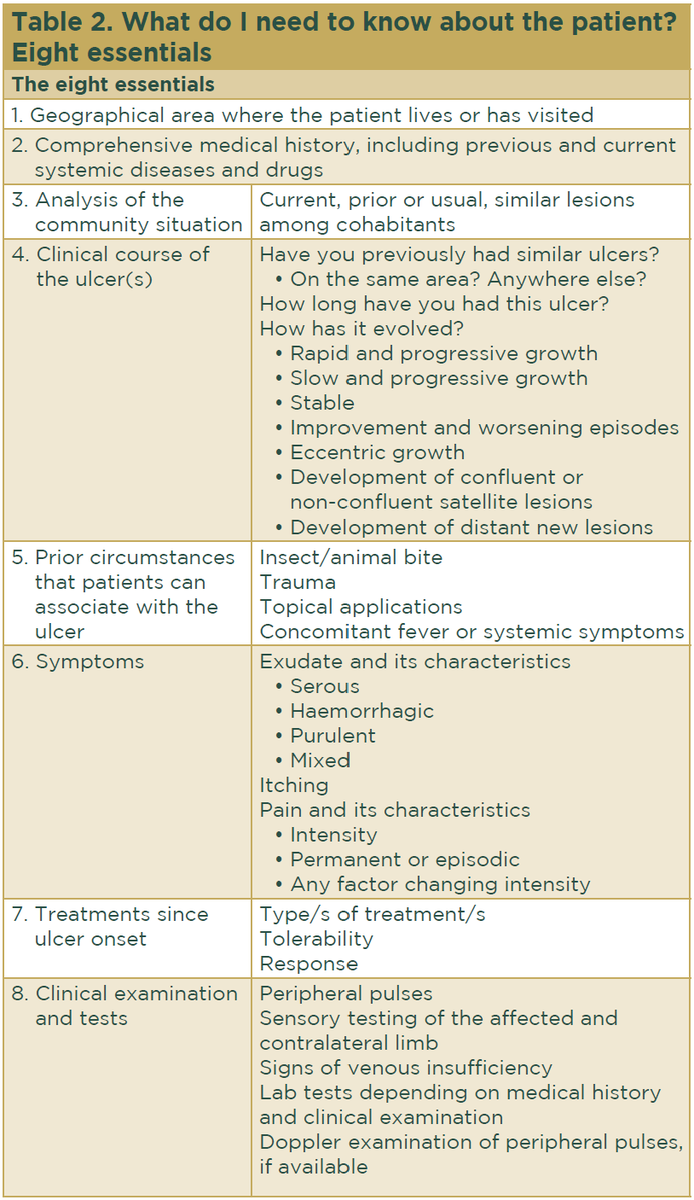

Clinicians face multiple difficulties in establishing the cause of skin ulcers (Table 1). Careful assessment of the clinical clues is an essential first step in determining the underlying cause and deciding on the most appropriate tests (Table 2).

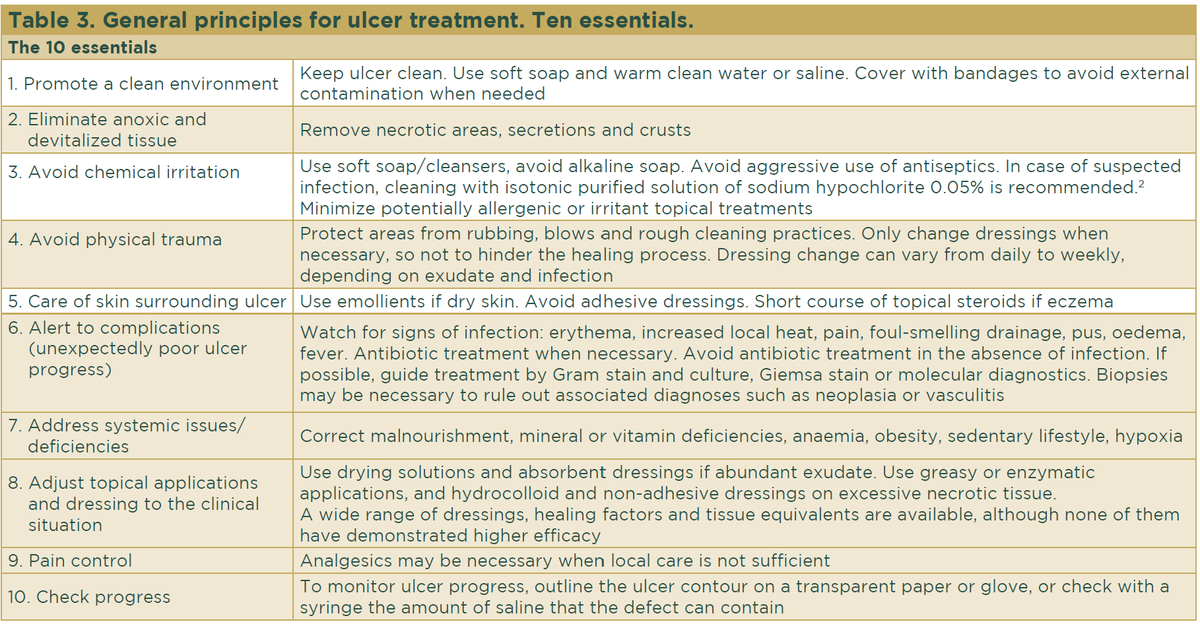

Regardless of the cause of skin ulcers, their clinical care is broadly similar (Table 3). In addition to these general care measures, the clinician should minimize avoidable harmful stimuli, 2 control the underlying pathology that hinders healing and implement specific treatment depending on the aetiology of the ulcer, as detailed in the sections below.

Venous ulcer

Venous leg ulcers, caused by venous insufficiency, are one of the most common lower limb ulcers. With a worldwide distribution, the estimated prevalence in the general population is 2%, rising to 5% among those > 65 years of age. These ulcers cause an important socioeconomic burden and a great psychological and physical impact on those affected.3 They are related to older age and are associated with a sedentary lifestyle and a genetic predisposition. Incompetence of the valves of the perforating veins connecting superficial and deep venous systems generates persistent high venous pressure. Clinical signs of venous insufficiency are purpura, hyperpigmentation, eczematization of surrounding skin, dermal fibrosis, an ‘inverted champagne bottle’ appearance of the leg and varicose veins. Venous ulcers follow an indolent clinical course, are frequently recurrent and are often related to external injury.

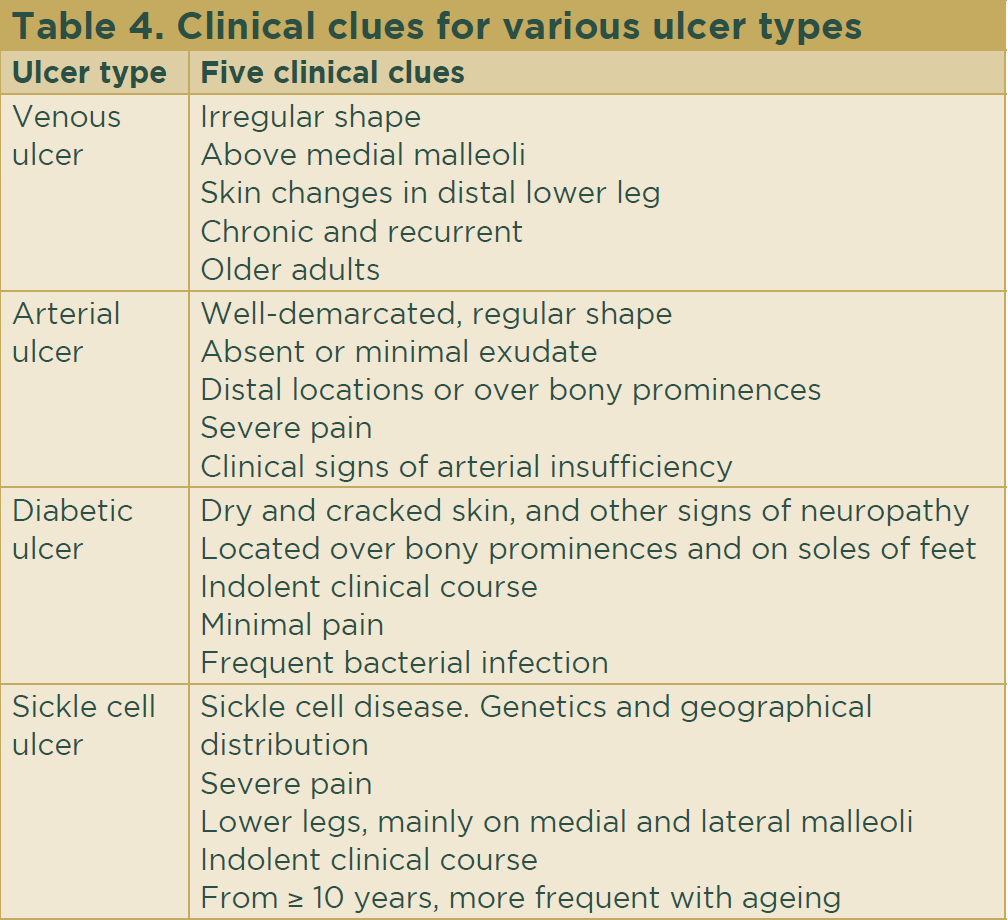

They are usually located on the medial lower leg, above the malleolus. Ulcers tend to be irregular in shape with well-defined borders (Fig. 1a). The ulcer bed has granulation and fibrinous tissue and may be covered by yellow–white exudate. Besides the previously described signs of venous insufficiency, the surrounding skin may show inflammatory signs. Associated pain may be absent, mild or extreme (Table 4). Specific treatment of venous ulcers is aimed at reducing venous pressure and gravitational reflux4 and includes the following.

- Exclude any associated arterial compromise, in which case compressive bandages cannot be used.

- If arterial compromise has been excluded, use compressive bandages. For lower leg ulcers, compression must be applied from the base of the toes to just below the knee joint.

- Elevate legs above the level of the heart while lying down.

- Surgical treatment, if correctable incompetent valves are detected.

Arterial ulcer

Diseases causing occlusion of arterial blood supply lead to necrosis, skin ulcers and delayed wound healing. The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the general population is around 3%, increasing up to 20% in individuals > 70 years. The underlying causes include atherosclerosis, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and vasculitis. Diabetes, family history of atherosclerosis and, chronic kidney disease are recognized risk factors, as is also being a person of skin of colour.5 Arterial ulcers are mainly located distally and over bony prominences, such as toes or the pretibial area. They are usually punched-out in appearance with well-demarcated borders, a necrotic ulcer bed and lack exudate or bleeding6 (Fig 1b). Other signs and symptoms of arterial impairment may be present and include changes in the surrounding skin (thin, shiny, hairless, dry, cold skin), toenails (hypertrophic, slow growing, brittle toenails), weak or absent peripheral pulses and exercise-induced calf pain alleviated by rest (intermittent claudication) (Table 4).

Venous and arterial insufficiency may coexist giving rise to a mixture of clinical features. Arterial ulcers cause severe pain that may worsen with limb elevation and in bed at night. Clinical suspicion is confirmed by determination of the ankle-brachial index and vascular imaging studies. Arterial ulcer treatment requires prevention and treatment of the underlying problems that compromise arterial flow (atherosclerosis, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia) and may also include referral for microvascular surgery.7

Diabetic neuropathic ulcer

Diabetes is considered a silent pandemic with increasing prevalence worldwide. Low- and middle-income countries account for the highest percentage of adults affected.8 Diabetic foot ulcer is a highly morbid complication affecting approximately 25% of those with diabetes. The incidence increases with age and poor control of diabetes. This figure is rising, especially among populations of people of skin of colour.9 Complex mechanisms of microvascular dysfunction and impaired wound healing play a role, but neuropathy and infection are the main contributing factors. Ulcers occur after unnoticed trauma because of impaired sensitivity.

On clinical examination, light touch sensation and proprioception (position sense) may be decreased or absent. On the other hand, autonomic neuropathy causes dryness and fissuring of skin leading to erosions, ulcers and subsequent infection. The clinical course and healing process are very slow. Diabetic ulcers are most common on the pressure points and soles of the feet and over bony prominences (Table 4 and Fig. 1c). They are usually surrounded by a callus and the borders are undermined. The ulcer bed is necrotic and may expose underlying structures. These ulcers tend to be covered by a haemorrhagic crust.

Wound infection is very common but the external signs of this complication (pain, exudation, local increase of temperature, oedema) can be subtle in these patients leading to difficulties in prompt detection. Untreated infection hinders the healing process and may spread to deeper tissues leading to bone infection necessitating amputation in some cases. Frequently, because of sensory impairment, diabetic ulcers are painless. Ulcers associated with other neuropathic conditions, like leprosy, share similar characteristics.

As a specific measure, prevention is the key objective. Affected individuals and their caregivers must be trained in specialized and thorough self-care of the feet. Good hygienic measures, gentle cleansing with a mild soap and gentle drying, the frequent use of emollients to keep the skin well moisturized and periodic check-ups to detect the presence of small skin breaks, calluses or toenail deformities early, are very important to control the condition before further progression. The use of appropriate footwear that correctly accommodates the structural deformities of the foot is essential to avoid foot injuries over pressure points from friction or trauma. From a general point of view, careful and close monitoring of diabetes is the most effective preventive measure. Surveillance for infection is important, using clinical observation and serum biomarkers for local or systemic signs of inflammation. If osteomyelitis is suspected, imaging techniques are necessary.

Sickle cell anaemia-related ulcers

Sickle cell anaemia is a group of autosomal recessive diseases characterized by the presence of a mutated haemoglobin (HbS), prevalent in people with skin of colour. There is morphological, sickle-shaped, distortion of erythrocytes that causes an increase in blood viscosity, slow flow in small vessels and tendency to trigger the coagulation cascade, subsequently leading to distal tissue ischaemia and ulceration. The clinical consequences are veno-occlusive crises and ulcers, both more frequent in homozygous individuals and in certain geographical areas, like Jamaica.

Leg ulcers are common and generate significant morbidity. Other types of anaemias (spherocytosis, thalassemia, iron deficiency etc), when severe, can lead to the same complication. Ulcers are related to the severity of haemolysis and other signs of advanced vasculopathy, such as pulmonary hypertension and priapism. Besides venous insufficiency, trauma, infections and anaemia are major facilitating factors. Hydroxyurea (used to treat sickle cell anaemia) is known to also cause skin ulcers.

Sickle cell ulcers are extremely painful. They usually appear after the age of 10 years, increase with age and are more frequent in males. The clinical course follows an indolent pattern. The ulcers are located in areas with little adipose tissue, thin skin and venous compromise, such as the medial malleolus (Table 4). Less frequently, they appear on the lateral malleolus, pretibial region, dorsum of the foot and Achilles region. The clinical characteristics of the ulcers are similar to those of venous ulcers.

The specific treatment measures include correction of anaemia to a level of unaltered Hb > 8 g/dL. Sometimes, red blood cell transfusion is needed. The eventual pathogenic role of hydroxyurea and its withdrawal from the patients’ treatment regime may have to be considered. It is important to control excessive venous pressure and to prevent trauma as described in the sections for venous and neuropathic ulcers. Pain management can be difficult and requires appropriate analgesics. Surgical treatment may be necessary and may include skin grafting.10

References

- Wysocki AB. Evaluating and managing open skin wounds: colonization versus infection. AACN Clin Issues 2002; 13:382–97.

- Maniscalco R, Mangano G, De Joannon AC et al. Effect of sodium hypochlorite 0.05% on MMP-9 extracellular release in chronic wounds. J Clin Med 2023; 12:3189.

- Raffetto JD, Ligi D, Maniscalco R et al. Why venous leg ulcers have difficulty healing: overview on pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and treatment. J Clin Med 2020; 10:29.

- Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Phillips TJ et al. What’s new: management of venous leg ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 74:627–40.

- Dean SM. Cutaneous manifestations of chronic vascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2018; 60:567–79.

- Buford L, Kaiser R, Petronic-Rosic V. Vascular diseases in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol 2018; 36:239–48.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2017; 135:e686–725.

- Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2019; 157:107843.

- McDermott K, Fang M, Boulton AJM et al. Etiology, epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 2023; 46:209–21.

- Monfort JB, Senet P. Leg ulcers in sickle-cell disease: treatment update. Adv Wound Care 2020; 9:348–56.