Optimizing nutrition intervention to enhance wound healing in low-resource settings

1 Dec 2024

Optimizing nutrition intervention to enhance wound healing

in low-resource settings

Authors: Samuel Nwafor [1], and Nancy Collins [2]

- Wound and Hyperbaric Medicine Center, Mountain Vista Medical Center, Mesa, AZ, USA.

- Light Bulb Health, Inc., Las Vegas, NV, USA.

Conflict of interest: None

Key words: Wound healing; nutrition; low-resource areas

Billions of people live in parts of the world where resources for adequate medical and nutritional care are unavailable. In these low-resource settings, management of chronic wounds is particularly challenging. Demographic patterns of chronic wounds in low-resource settings across the world show diverse wound aetiologies, including diabetic foot wounds, pressure injuries, vascular lower extremity wounds, burns and complications of acute bacterial soft tissue infections and wounds caused by chronic skin infections and neglected tropical diseases.

The medical and nutritional treatments of these wounds are often hindered because of the lack of wound-care-certified staff, food deserts, scarcity of supplies and lack of knowledge regarding the link between nutrition and wound healing. In certain parts of the world, nutritional optimization sometimes is complicated further by poverty, famine and even violence.

Delayed wound healing and poor wound outcomes are almost guaranteed in the presence of poor nutritional intake and malnutrition. It is imperative that patients with wounds consume an adequate amount of both macronutrients and micronutrients daily to fuel the wound-healing process and build new tissue. In clinical practice, providers must determine the nutritional status of their patients by conducting an initial nutrition screening to identify those at risk and those with pre-existing malnutrition. A comprehensive nutrition assessment should follow the screening to develop a realistic intervention plan appropriate for the available resources.

Overview of the wound-healing process

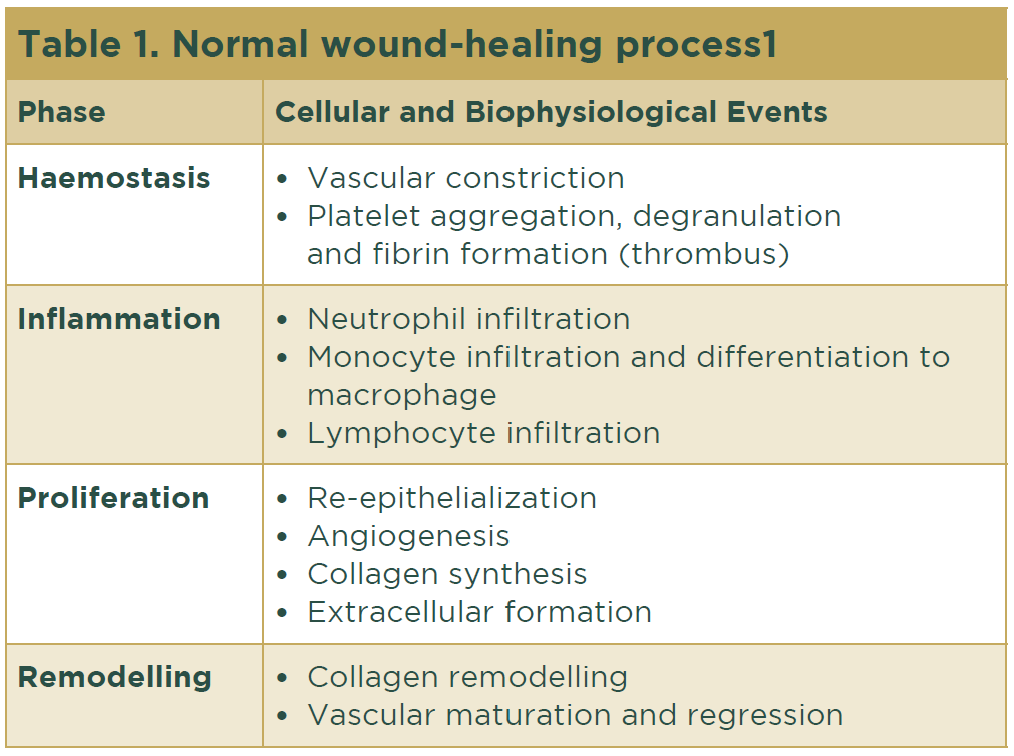

Normal wound healing has four overlapping stages – haemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and maturation. The initial stage of wound healing involves the action of platelets and fibrin meshwork to achieve haemostasis around the injury. The subsequent inflammatory phase involves neutrophils, lymphocytes and macrophages, which mount an immune response in the wounded area. During the proliferative phase, fibroblasts enter and proliferate in the wound site where they secrete collagen molecules. This newly formed matrix is host to angiogenesis and in its final step, the wound edges are drawn together. The final phase includes remodelling and contraction to create tissue maturation.

These phases and their biophysiological functions must occur in the proper sequence at a specific time and continue for a specific duration at an optimal intensity. Many factors can affect wound healing and interfere with one or more phases in this process, thus causing improper or impaired tissue repair.1 Table 1 summarizes the cellular and biophysiological events of each stage.

Nutrition screening and assessment

Nutrition screening is the process of identifying patients who may have a nutrition diagnosis and benefit from nutrition assessment and intervention by a registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN), if one is available.2 Nutrition screening is critical in all patients with wounds at the first encounter, whether in an inpatient or long-term care facility setting, an outpatient wound centre or community health clinic. A variety of validated nutrition screening tools are available free of charge, making this first step of the nutrition care process easily achievable, even in low-resource settings. Some common screening tools include the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST), the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST), the Mini Nutrition Assessment – Short Form (MNA–SF) and the Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire (SNAQ).3 Any member of the healthcare team can perform these screenings. Most tools take just a few minutes to complete and include a series of questions focusing on weight status, food intake, medical conditions and related topics.

Following the screening, a referral to an RDN is made if indicated and the resource is available. The RDN will then conduct a complete nutrition assessment, which includes assessment of anthropometric, biochemical and diet history data, as well as relevant socioeconomic information that may affect food intake. In low-resource settings, laboratory tests sometimes are not available, so a combination of nutritional intake history and careful assessment of anthropometric parameters, including a nutrition-focused physical examination, is preferred. Laboratory testing for hepatic proteins, such as albumin and prealbumin, is shown to reflect the inflammatory process more than nutritional status, so these laboratory tests are no longer recommended as part of the nutrition assessment.4 After the assessment is completed, an appropriate plan of care is started in coordination with the multidisciplinary team.

Oral nutritional supplements

Oral nutritional supplements (ONSs) are nutrient-dense products used to fill in gaps in a patient’s diet. High-calorie, high-protein ONSs can also serve as a meal replacement. These products are commercially available in a variety of forms, including beverages, puddings, jellied products, bars and powders for adding to water or other liquids, and come in a variety of flavours. It is imperative to find a product that the patient will consume in its entirety to avoid waste, particularly in low-resource settings.

Wound healing-specific formulas contain nutritional components that are important in the wound-healing process, such as arginine, vitamin C, zinc and specific collagen dipeptides, including prolyl-hydroxyproline (PO) and hydroxyprolyl-glycine (OG).5 Some products contain citrulline as a precursor to arginine. Approximately 80% of citrulline is converted to arginine in the kidneys.6 Current research suggests that these products can improve healing, and a recommendation for such is included in the current version of the Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline, issued jointly by the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. The guideline recommends provision of a high-calorie, high-protein, arginine, zinc and antioxidant ONS or enteral formula for adults with a stage 2 or greater pressure injury who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition.7

In low-resource settings these commercial products are sometimes not available or may simply cost too much, making it necessary to employ strategies that use local or homemade products. It is possible to make similar high-calorie, high-protein milkshakes from whole milk and ice cream.

Adapting nutrition wound care guidance in a low-resource setting

Protein: Protein is the macronutrient most closely tied to wound healing for many reasons. Protein, a complex nitrogenous compound made up of amino acids in peptide linkages, is essential for life. Proteins carry out the work of the cell by serving as enzymes, receptors, transporters, hormones, antibodies or communicators that build, maintain and repair body tissues.8

The typical protein recommendation for patients who have wounds with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition ranges from 1.25 to 1.5 g/kg of bodyweight daily.7 In simple terms, this equates to about 280 – 340g for a 57–66 Kg patient (or approx. 10 – 12 oz for a 125 - 145 lb patient). To meet this goal in low-resource settings, the recommendation is to suggest lower cost protein foods, such as tinned fish (e.g. sardines, tuna fish), peanut butter, lentils, beans, chicken drumsticks, ground beef and amaranth.

Vitamin C: Citrus fruits, including oranges, lemons, limes and tangerines, are abundant in many geographic areas, even those with low resources. The high vitamin C content of citrus fruits makes them ideal to provide vitamin C, which is a necessary daily cofactor for wound healing (Figs. 1 and 2).

L-citrulline and arginine: Food sources of citrulline are not abundant, with watermelon having the highest content of L-citrulline.9 L-citrulline is a precursor of arginine and currently is used extensively in commercial preparations of amino acid supplements because it provides higher levels of bioavailable arginine. Watermelon is an alternative where available.

Zinc: Zinc is a cofactor for many metalloenzymes required for cell membrane repair, cell proliferation, growth and immune system function. As a cofactor for RNA and DNA polymerase, it is also involved in DNA synthesis, protein synthesis and cellular proliferation.10 Zinc-rich foods are strongly encouraged. Food sources high in zinc include oysters, chicken legs, lean pork chops, lentils, oatmeal, beef (chuck), firm tofu, hemp seeds, wheat germ and mushrooms.11 It is possible to replace a commercial zinc supplement with a diet containing adequate zinc foods throughout the week.

Antioxidants: Rather than relying on commercial supplements, many people in low-resource areas can rely on local plants and spices, including turmeric (Fig. 3), oregano and moringa (Fig. 4).

Curcumin, the active ingredient in turmeric, has significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Turmeric has a long history of therapeutic application in traditional Asian medicine. Turmeric is often called the golden spice because of its brilliant yellow colour. Others refer to it as Indian saffron. In wound healing, turmeric intake may enhance granulation tissue formation, collagen deposition, tissue remodelling and wound contraction.12 This spice is readily available in many areas.

Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) is a common flowering plant cultivated all over the world, including several geographical areas in low-resource settings. Oregano extract has cytotoxic, antioxidant and antibacterial activities mostly attributed to carvacrol and thymol.13 Studies show that oregano improves wound healing through its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, as well as anti-collagenase and anti-elastase effects and the promotion of tissue remodelling and re-epithelialization.14

Moringa oleifera is a plant native to northern India that also grows in other tropical and subtropical places, such as Asia and Africa. Folk medicine has used the leaves, flowers, seeds and roots of this plant for centuries.15 Moringa is reported as an important element in controlling diabetes. Moringa leaves are noted as a significant agent in reducing the blood glucose level immediately after it is taken.16 The extracts (aqueous) from moringa show significant pro-healing actions, which may have a role in treating diabetic foot ulcers.17

Hydration: Safe, potable water is difficult to obtain in some low-resource areas, but proper hydration is necessary for wound healing. If water or other fluids are not available, the best advice is to consume foods with a high-water content, such as cucumbers, cantaloupe watermelon, lettuce, tomatoes, cabbage, celery, spinach and summer squash/zucchini.

Nutrition education and implementation

Low-resource environments tend to lack adequate specialized staffing teams and hence are unlikely to have RDNs to manage and monitor nutritional interventions in patients with wounds. The use of trained local health educators is of immense value in patient nutrition education helping to improve wound-healing outcomes. No matter how low resource the setting is in terms of infrastructure and materials, concerned and compassionate human beings always can do something of value. The most precious resource available in these circumstances is other people.18

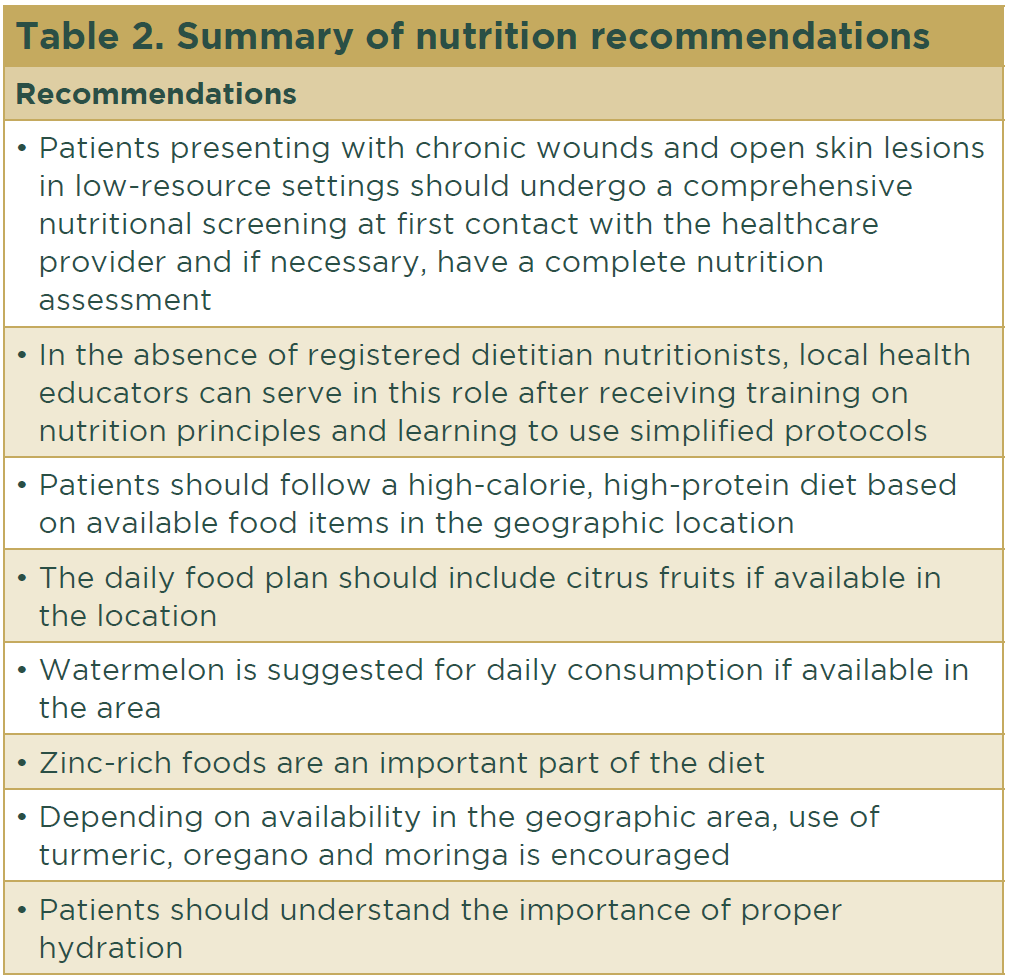

The development of simple nutritional protocols based on the current recommendations but using available food items should become part of the treatment plan for patients. Table 2 summarizes the recommendations. Rather than high-cost supplements, homemade foods can often provide the necessary nutrients at a lower cost. The key to a successful nutrition programme is learning the basic principles of nutrition and wound healing and then developing a plan to meet nutritional needs with what is available in the local area.

References

- Mathieu D, Linke J-C, Wattel F . Non-healing wounds. In: Handbook on Hyperbaric Medicine (Mathieu DE, ed). Dorderecht: Springer, 2006; 401–27.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Evidence Analysis Library®. Nutrition screening adults: welcome to the nutrition screening adults systematic review. Available at: https://www.andeal.org/topic.cfm?menu=5382#:~:text=Nutrition%20screening%20is%20the%20process,registered%20dietitian%20nutritionist%20(RDN) (last accessed 7 September 2024).

- Skipper A, Coltman A, Tomesko J et al. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: malnutrition (undernutrition) screening tools for all adults. J Acad Nutrit Dietetics 2020; 120:709–13.

- Marcason W. Should albumin and prealbumin be used as indicators for malnutrition? J Acad Nutrit Dietetics 2017; 117:1144.

- Sugihara F, Inoue N, Venkateswarathirukumara S. Ingestion of bioactive collagen hydrolysates enhanced pressure ulcer healing in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical study. Sci Rep 2018; 8:11403.

- Agarwal U, Didelija IC, Yuan Y et al. Supplemental citrulline is more efficient than arginine in increasing systemic arginine availability in mice. J Nutr 2017; 147:596–602.

- European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guidelines. EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019. Available at: https//internationalguideline.com (last accessed 7 September 2024).

- LibreTexts™ Medicine. Functions of protein. Available at: https://med.libretexts.org/Courses/Metropolitan_State_University_of_Denver/Introduction_to_Nutrition_(Diker)/06%3A_Proteins/6.05%3A_Proteins_Functions_in_the_Body (last accessed 7 September 2024).

- Manivannan A, Lee E-S, Han K et al. Versatile nutraceutical potentials of watermelon—a modest fruit loaded with pharmaceutically valuable phytochemicals. Molecules 2020; 25:5258.

- Lin PH, Sermersheim M, Li H et al. Zinc in wound healing modulation. Nutrients 2018; 10:16.

- US Dept of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. MyFoodData: foods highest in zinc. https://www.myfooddata.com/articles/high-zinc-foods.php (last accessed 1 September 2024).

- Akbik D, Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R. Curcumin as a wound healing agent. Life Sci 2014; 116:1–7.

- Coccimiglio J, Alipour M, Jiang ZH et al. Antioxidant, antibacterial, and cytotoxic activities of the ethanolic Origanum vulgare extract and its major constituents. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016; 2016:1404505.

- Bora L, Avram S, Pavel IZ et al. An up-to-date review regarding cutaneous benefits of Origanum vulgare L. essential oil. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022; 11:549.

- Islam Z, Islam SMR, Hossen F et al. Moringa oleifera is a prominent source of nutrients with potential health benefits. Int J Food Sci 2021; 2021:6627265.

- Mittal M, Mittal P, Agarwal A. Pharmacognostical and phytochemical investigation of antidiabetic activity of Moringa oleifera lam leaf. Indian Pharm 2007; 6:70–2.

- Rathi BS, Bodhankar SL, Baheti AM. Evaluation of aqueous leaves extract of Moringa oleifera Linn for wound healing in albino rats. Indian J Exp Biol 2006; 44:898–901.

- Goldstuck N. Healthcare in low-resource setting: the individual perspective. Healthcare Low-resource Settings 2014; 2:4572.